Additional Games

- Chessgames

- Game, Gottfried Reinhardt vs. Alexander Bisno, Bisno-Reinhardt Match Round 1, 1950.

- Game, Alexander Bisno vs. Gottfried Reinhardt, Bisno-Reinhardt Match Round 2, 1950.

- Game, Gottfried Reinhardt vs. Alexander Bisno, Bisno-Reinhardt Match Round 3, 1950.

- Game, Gottfried Reinhardt vs. Lodewijk Prins, Prins Exhibition, 1951.

- Game, Samuel Reshevsky vs. Gottfried Reinhardt, Reshevsky Exhibitions, 1952.

Gottfried Reinhardt 20 Jul 1994, Wed The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

Gottfried Reinhardt 20 Jul 1994, Wed The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

Warming Up 17 Aug 1941, Sun The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

Warming Up 17 Aug 1941, Sun The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

WARMING UP— Gottfried Reinhardt, producer, left, and Edward G. Robinson practice their chess in preparation for the benefit exhibition to be held Sept. 7 at Hollywood Athletic Club, in which Herman Steiner, Times chess editor, will play 400 opponents.

Chess Player to Vie With 400 17 Aug 1941, Sun The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

Chess Player to Vie With 400 17 Aug 1941, Sun The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

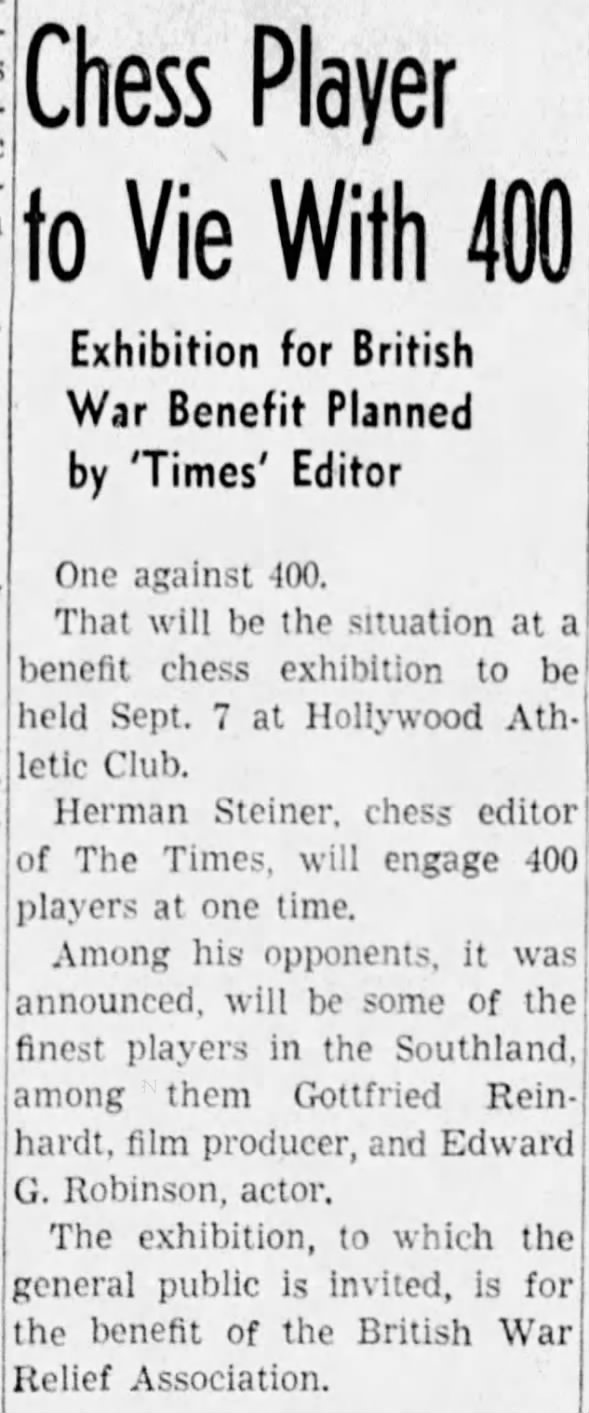

Chess Player to Vie With 400

Exhibition for British War Benefit Planned by 'Times' Editor

One against 400.

That will be the situation at a benefit chess exhibition to be held Sept. 7 at Hollywood Athletic Club.

Herman Steiner, chess editor of The Times, will engage 400 players at one time.

Among his opponents, it was announced, will be some of the finest players in the Southland, among them Gottfried Reinhardt, film producer, and Edward G. Robinson, actor.

The exhibition, to which the general public is invited, is for the benefit of the British War Relief Association.

Produced and Directed by Gottfried Reinhardt 06 Dec 1965, Mon Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) Newspapers.com

Produced and Directed by Gottfried Reinhardt 06 Dec 1965, Mon Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) Newspapers.com

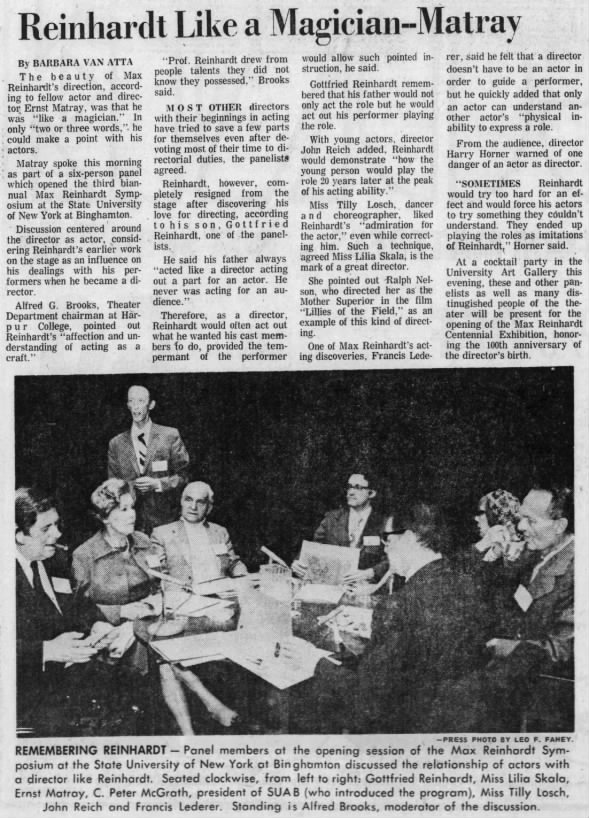

Reinhardt Like A Magician--Matray 18 May 1973, Fri Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York) Newspapers.com

Reinhardt Like A Magician--Matray 18 May 1973, Fri Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York) Newspapers.com

Gottfried Reinhardt, Producer-Director, Dies 20 Jul 1994, Wed The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

Gottfried Reinhardt, Producer-Director, Dies 20 Jul 1994, Wed The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) Newspapers.com

Gottfried Reinhardt, Producer-Director, Dies

By Burt A. Folkart, Times Staff Writer

Gottfried Reinhardt, producer of several well-known films, biographer of his internationally celebrated father, Max, and himself the parent of a distinguished jurist, died Tuesday.

A family spokeswoman said Reinhardt was 81 and died at his Brentwood home of pancreatic cancer.

Known to movie fans as the producer of several films, among them “Two-Faced Woman,” Greta Garbo's last movie, and “Situation Hopeless but Not Serious,” Robert Redford's first, Reinhardt was a legend among industry insiders as one of Hollywood's pioneering and most successful hyphenates: writer-producer-director.

His reign in pictures saw the rise and dominance of Louis B. Mayer at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where Reinhardt labored throughout the 1930s, and the demise of the handful of moguls who, like Mayer, held stars, writers and directors with often unrewarding but tightly written contracts and threats of banishment.

Yet in an interview for the Lillian Ross book “Picture,” a widely heralded 1952 account of the making of one of Reinhardt's epics, “The Red Badge of Courage,” he seemed to lament the passing of the efficacy of the old regime: “Everybody in Hollywood wants to be something he is not. . . .The writers want to be directors. The producers want to be writers. The actors want to be producers. . . . Everybody is frustrated. Nobody is happy.”

Reinhardt evolved from being a screenwriter of the 1935 film “I Live My Life,” learning how to direct and produce from such giants as Ernst Lubitsch and Walter Wanger, respectively.

He was raised in his father's shadow Max Reinhardt was considered Germany's most important stage producer and director during the first three decades of the century and said in a 1982 Times interview that his relocation to the United States was “a fluke.”

He had heard about the ascendancy of Adolf Hitler while riding the subway in New York on a 1931 vacation. “I never went home,” he said. His Jewish father had also emigrated, first to Austria and then to the United States, but both men found Broadway mired in the Depression so both eventually came to Hollywood. (Gottfried Reinhardt later wrote several Broadway plays, among them “Rosalinda” and “Helen Goes to Troy.”)

Max Reinhardt made a film of his famed “A Midsummer Night's Dream” and produced a spectacular version of the drama at the Hollywood Bowl while his son, who spoke excellent English, found work with Lubitsch. Gottfried Reinhardt also helped arrange visas for Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht, fellow Germans who had been forced to flee Hitler. But cultural differences prevented the two writing giants from assimilating into the film community, while Reinhardt adapted more easily and found regular work at MGM.

During World War II, he served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps making documentaries. By 1950, when he began work on “Red Badge,” Reinhardt had produced “Comrade X,” “Rage in Heaven” and “Command Decision.” Actors in his films included Clark Gable, Lana Turner, Alec Guinness, Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas.

It was on the “Red Badge” set that Reinhardt saw Mayer undermined and overruled.

The Founding Father of MGM had refused to let Reinhardt make the relatively high-budget Civil War drama, but Dore Schary went to New York executives and had the picture reinstated. Reinhardt recalled the incident as a turning point in the decline of Mayer's influence.

After that Reinhardt left MGM and went to Europe, where he made several German and French pictures before returning for Redford's 1965 debut in films. He directed at the Salzburg Festival, which was founded by his father, and wrote a loving tribute to his father: “The Genius: A Memoir of Max Reinhardt” in 1979. And he lived to see his son, Judge Stephen Reinhardt, become one of the most outspoken members on the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. A major figure in Los Angeles Democratic politics for three decades, Stephen Reinhardt became known for controversial rulings that often put him at odds with the conservative wing of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Reinhardt is also survived by his wife, Silvia, three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. His daughter-in-law is Ramona Ripston, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

Funeral services are scheduled for 11 a.m. Thursday at Hillside Memorial Park.