April 14 1969

June 17 1969

Spassky Crowned New Chess Champ 17 Jun 1969, Tue The Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) Newspapers.com

Spassky Crowned New Chess Champ 17 Jun 1969, Tue The Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) Newspapers.com

The Vancouver Sun Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Tuesday, June 17, 1969 ★

Spassky Crowned New Chess Champ

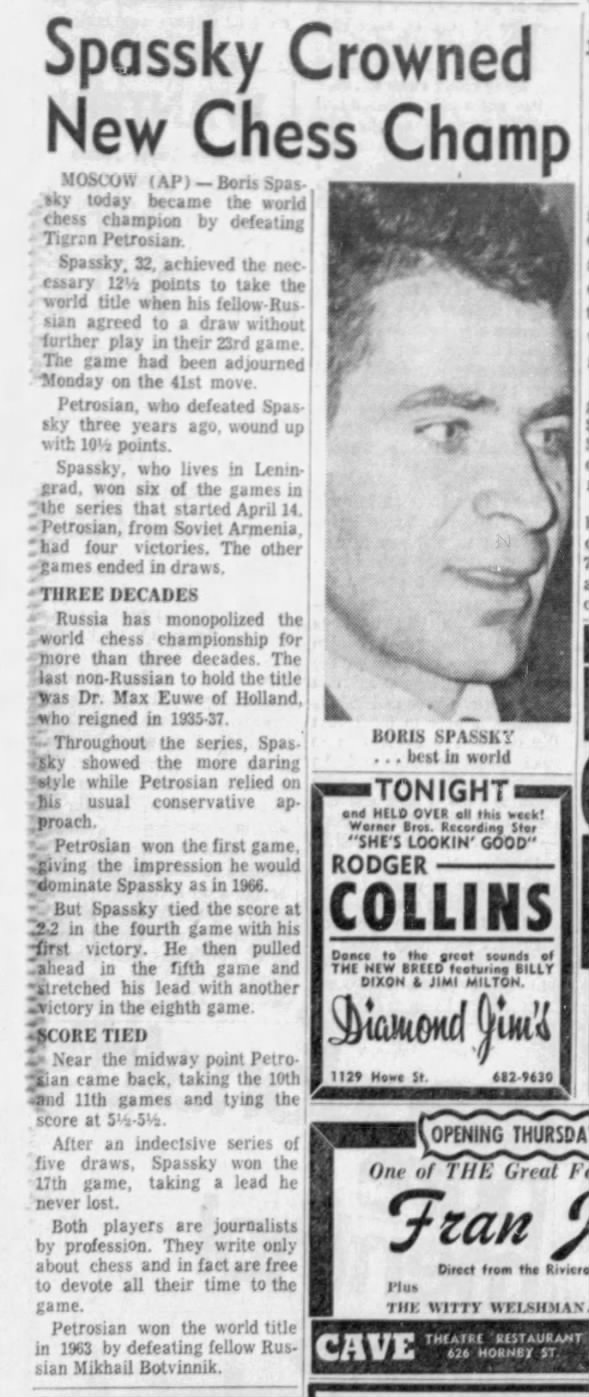

Moscow (AP) — Boris Spassky today became the world chess champion by defeating Tigran Petrosian.

Spassky, 32, achieved the necessary 12½ points to take the world title when his fellow-Russian agreed to a draw without further play in their 23rd game. The game had been adjourned Monday on the 41st move.

Petrosian, who defeated Spassky three years ago, wound up with 10½ points.

Spassky, who lives in Leningrad, won six of the games in the series that started April 14. Petrosian, from Soviet Armenia, had four victories. The other games ended in draws.

Three Decades

Russia has monopolized the world chess championship for more than three decades. The last non-Russian to hold the title was Dr. Max Euwe of Holland who reigned in 1935-37.

Throughout the series, Spassky showed the more daring style while Petrosian relied on his usual conservative approach.

Petrosian won the first game, giving the impression he would dominate Spassky as in 1966.

But Spassky tied the score at 2-2 in the fourth game with his first victory. He then pulled ahead in the fifth game and stretched his lead with another victory in the eighth game.

Score Tied

Near the midway point Petrosian came back, taking the 10th and 11th games and tying the score at 5½-5½.

After an indecisive series of five draws, Spassky won the 17th game, taking a lead he never lost.

Both players are journalists by profession. They write only about chess and in fact are free to devote all their time to the game.

Petrosian won the world title in 1963 by defeating fellow Russian Mikhail Botvinnik.

June 18 1969

The Guardian London, Greater London, England Wednesday, June 18, 1969

Mate at Last - Leonard Barden on the New Chess Champion

BORIS SPASSKY is the archetype of a Soviet wonder boy; handsome and athletic enough for a hair-cream advertisement he is the very antithesis of the public's view of a chess master as a balding septuagenarian who takes an hour to push a pawn. The new world champion from Leningrad is only 32 and spent his university years as a volley ball halfback and a high jumper.

Many leading players, Tigran Petrosian (the Armenian whom he beat on Monday) included, have the pragmatic, day to day, somewhat materialistic attitudes typical of professional sportsmen; it is just that their field of activity happens to be mental rather than physical. Others, like the former champions Botvinnik, Tal, and Smyslov, are intellectual scientists or artistic dreamers who use the chess-board as the mechanism for their achievement.

Spassky is more complex. In his personality there is often a kind of deep introspective and rather sorrowing quality, even in inappropriate, situations. The Tass commentator remarked that Petrosian appeared relaxed and satisfied when he went to the Central Chess Club to resign the eighth game and go two down, but that the winner Spassky looked careworn and depressed.

Spassky has become world champion at what is generally regarded as the prime of a chess master's life, and it is easy to overlook that he was once considered likely to be the youngest ever champion, and a little later seemed a failed talent.

He learnt the moves when he was five, but then forgot about chess for several years. In 1946 he happened to see games in progress at an open air chess pavilion in Leningrad's Central Park, and his interest revived.

He made rapid progress, coached by a veteran Leningrad master Zak. At 14, he was a candidate master; at 15, he was spoken of as the Soviet Union's most exciting young prospect; at 16, he played with distinction in a strong international tournament at Bucharest; at 18, he was world junior champion.

Youngest player

The same year, 1955, he became the youngest player ever to qualify for the senior world title interzonal tournament, and in 1956, at 19 he was one of the eight challengers who played in Amsterdam for the right to challenge the then champion Botvinnik. Spassky expected little from himself then: “I was very calm, and I understand that I was a very weak player among this company; but I had to fight.” He finished equal second with an enhanced reputation.

At the start of 1958 Spassky played a game which haunted him for years and began the most unhappy period of his life. The USSR championship of that year, held in Riga, was a qualifying tournament for the next interzonal, and in the last round Boris had to meet a young Latvian named Mikhail Tal, who was playing inspired chess in front of his home town supporters in defense of the title which he had won the previous year. Spassky needed a win to be sure of an interzonal place; Tal a win to stay champion. The bitterly fought game was adjourned after 40 moves, and both players stayed up all night to analyze.

Boris described to me what happened: “When I played very important games I usually tried to bathe, to put on a very good shirt and suit. But this time I had analyzed a great deal and came to the board looking very disheveled and tired. Then I was like a stubborn mule: I remember that Tal offered me a draw, but I refused.

“When I lost the game there was a thunder of applause, but I was in a daze and hardly understood. I was certain the world went down; I felt there was something terribly wrong. After this game, I went on the street and cried like a child.”

In this period, also, Spassky was out of favor with Soviet chess officials. In 1960 the world students tournament was held in Leningrad; Spassky was the Russian top board but, deep in his crisis of form, he lost with White to the United States No. 1, William Lombardy, in only 25 moves. The Americans won the tournament, and Spassky carried the can.

It was in 1961 that Spassky took what he thinks was the most positive step in his chess career; he started to analyze and work with Igor Bondarevsky, the grandmaster who is his coach and trainer. Bondarevsky used a different method and with his sympathetic handling Spassky gradually regained the confidence and poise which had disappeared with the defeat by Tal in 1958.

Future problem

Spassky's path to the championship in the last five years, with the narrow defeat by Petrosian in 1966 as the only blemish in a run of victories against other leading contenders, is well known and does not require repetition. His future problem can be stated in two words: Bobby Fischer.

The American grandmaster, already a legend at the age of 24, is the only serious challenger whom Spassky has not already beaten in a match. But Fischer's almost paranoid view of Russian chess is well known, and after his refusal to play in the title elimination series in 1964 followed by his withdrawal in 1967 (written, according to whose account you follow, either on the back of the dinner menu or on the hotel toilet paper), it is very doubtful whether he will ever qualify to meet Spassky by the official means.

Yet as long as Fischer is around, one cannot say for sure that Spassky is the best player in the world as well as being world champion. Two international grading lists bracket Spassky and Fischer jointly at the top; Petrosian in a recent interview rated Fischer as the world No. 4 below Korchnoi but ahead of Larsen and Tal. I suspect the truth is somewhere between these extremes, and would give Spassky a 6-4 on chance to beat Fischer in a match.

He has said that even if he won the title he could never expect to be a chess giant dominating his contemporaries in the same way as Alekhine, Capablanca, Lasker, and Botvinnik.

Today a grandmaster can only be the first among equals; three or four years after reaching my peak I shall start to deteriorate and there will be some other strong player. Yet in talent Spassky could well be the equal of other great world champions; how much further he can go will depend to some degree on whether he now feels his ambitions are satisfied, and partly on what happens to Bobby Fischer.