October 16 2017

William Lombardy 16 Oct 2017, Mon The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) Newspapers.com

William Lombardy 16 Oct 2017, Mon The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) Newspapers.com

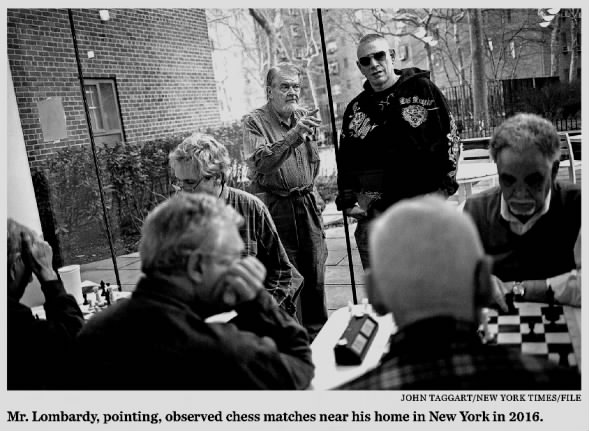

Mr. Lombardy, pointing, observed chess matches near his home in New York in 2016.

William Lombardy, 79, chess grandmaster turned priest 16 Oct 2017, Mon The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) Newspapers.com

William Lombardy, 79, chess grandmaster turned priest 16 Oct 2017, Mon The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) Newspapers.com

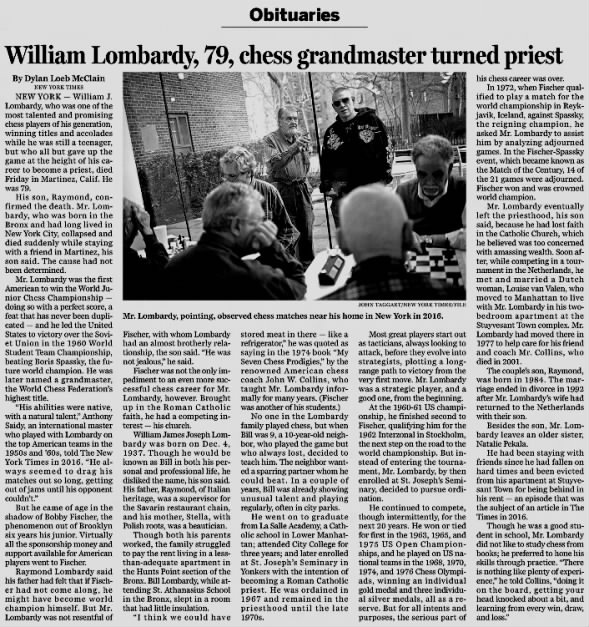

William Lombardy, 79, chess grandmaster turned priest

By Dylan Loeb McClain

NEW YORK TIMES

NEW YORK - William J. Lombardy, who was one of the most talented and promising chess players of his generation, winning titles and accolades while he was still a teenager, but who all but gave up the game at the height of his career to become a priest, died Friday in Martinez, Calif. He was 79.

His son, Raymond, confirmed the death. Mr. Lombardy, who was born in the Bronx and had long lived in New York City, collapsed and died suddenly while staying with a friend in Martinez, his son said. The cause had not been determined.

Mr. Lombardy was the first American to win the World Junior Chess Championship doing so with a perfect score, a feat that has never been duplicated and he led the United States to victory over the Soviet Union in the 1960 World Student Team Championship, beating Boris Spassky, the future world champion. He was later named a grandmaster, the World Chess Federation's highest title.

“His abilities were native, with a natural talent,” Anthony Saidy an international master who played with Lombardy on the top American teams in the 1950s and '60s, told The New York Times in 2016. “He always seemed to drag his matches out so long, getting out of jams until his opponent couldn't.”

But he came of age in the shadow of Bobby Fischer, the phenomenon out of Brooklyn six years his junior. Virtually all the sponsorship money and support available for American players went to Fischer.

Raymond Lombardy said his father had felt that if Fischer had not come along, he might have become world champion himself. But Mr. Lombardy was not resentful of Fischer, with whom Lombardy had an almost brotherly relationship, the son said. “He was not jealous,” he said.

Fischer was not the only impediment to an even more successful chess career for Mr. Lombardy, however. Brought up in the Roman Catholic faith, he had a competing interest — his church.

William James Joseph Lombardy was born on Dec. 4, 1937. Though he would be known as Bill in both his personal and professional life, he disliked the name, his son said. His father, Raymond, of Italian heritage, was a supervisor for the Savarin restaurant chain, and his mother, Stella, with Polish roots, was a beautician.

Though both his parents worked, the family struggled to pay the rent living in a less-than-adequate apartment in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx. Bill Lombardy, while attending St. Athanasius School in the Bronx, slept in a room that had little insulation.

“I think we could have stored meat in there like a refrigerator,” he was quoted as saying in the 1974 book “My Seven Chess Prodigies,” by the renowned American chess coach John W. Collins, who taught Mr. Lombardy informally for many years. (Fischer was another of his students.)

No one in the Lombardy family played chess, but when Bill was 9, a 10-year-old neighbor, who played the game but who always lost, decided to teach him. The neighbor wanted a sparring partner whom he could beat. In a couple of years, Bill was already showing unusual talent and playing regularly, often in city parks.

He went on to graduate from La Salle Academy, a Catholic school in Lower Manhattan; attended City College for three years; and later enrolled at St. Joseph's Seminary in Yonkers with the intention of becoming a Roman Catholic priest. He was ordained in 1967 and remained in the priesthood until the late 1970s.

Most great players start out as tacticians, always looking to attack, before they evolve into strategists, plotting a long-range path to victory from the very first move. Mr. Lombardy was a strategic player, and a good one, from the beginning.

At the 1960-61 US championship, he finished second to Fischer, qualifying him for the 1962 Interzonal in Stockholm, the next step on the road to the world championship. But instead of entering the tournament, Mr. Lombardy, by then enrolled at St. Joseph's Seminary, decided to pursue ordination.

He continued to compete, though intermittently, for the next 20 years. He won or tied for first in the 1963, 1965, and 1975 US Open Championships, and he played on US national teams in the 1968, 1970, 1974, and 1976 Chess Olympiads, winning an individual gold medal and three individual silver medals, all as a reserve. But for all intents and purposes, the serious part of his chess career was over.

In 1972, when Fischer qualified to play a match for the world championship in Reykjavik, Iceland, against Spassky, the reigning champion, he asked Mr. Lombardy to assist him by analyzing adjourned games. In the Fischer-Spassky event, which became known as the Match of the Century, 14 of the 21 games were adjourned. Fischer won and was crowned world champion.

Mr. Lombardy eventually left the priesthood, his son said, because he had lost faith in the Catholic Church, which he believed was too concerned with amassing wealth. Soon after, while competing in a tournament in the Netherlands, he met and married a Dutch woman, Louise van Valen, who moved to Manhattan to live with Mr. Lombardy in his two-bedroom apartment at the Stuyvesant Town complex. Mr. Lombardy had moved there in 1977 to help care for his friend and coach Mr. Collins, who died in 2001.

The couple's son, Raymond, was born in 1984. The marriage ended in divorce in 1992 after Mr. Lombardy's wife had returned to the Netherlands with their son.

Besides the son, Mr. Lombardy leaves an older sister, Natalie Pekala.

He had been staying with friends since he had fallen on hard times and been evicted from his apartment at Stuyvesant Town for being behind in his rent an episode that was the subject of an article in The Times in 2016.

Though he was a good student in school, Mr. Lombardy did not like to study chess from books; he preferred to hone his skills through practice. “There is nothing like plenty of experience,” he told Collins, “doing it on the board, getting your head knocked about a bit, and learning from every win, draw, and loss.”