April 20 1958

Corpus Christi Caller-Times, Corpus Christi, Texas, Sunday, April 20, 1958

Chess Players I Have Met by George Koltanowski

The principal English players of the present day can hardly be accused of having polychromatic personalities—in fact they are decidedly sub-fuse. But there is one rousing and pleasing exception, and that is Gerald Abrahams.

He is a lawyer and practices in Liverpool. He played for Oxford against Cambridge in 1927 and two years later was considered good enough to take part in the first of many British Championships that he has adorned. “He played,” we are told, “with a youthful vigor that aroused admiration even when it failed to succeed.” His style of play, it is clear, was already formed, and the passing of years has not changed it in the least.

“Toujours l'attaque” is his motto. Curiously enough, he generally plays rather stolid openings, though, as we shall see, he sometimes makes incursions into Tartakower's preserves. But after some Queen's Pawn game has dragged its weary length for some 15 moves or so, Abrahams spies an opportunity for a demonstration. A few more moves and all is changed; there are alarums and excursions; Bishops and Knights hurry to KN5 or KR6; Rooks are left en prise with the utmost abandon—in short, there is a devil-may-care melee. Very often it succeeds, for Abrahams has imagination and resource; but there are occasions when he will look round a shattered field and say, in almost an injured tone, “Why, I'm two pieces down—it's hardly worth my going on, is it?” “Talent without discipline” is how Golombek once described his play. He will never, I think, win the British championship, but he will always be one of the most dangerous of opponents.

A Genial Player

In appearance Abrahams has retained most of his youthful slimness, and his curly black hair is only beginning to grey above his plump and cheerful face. He is one of the most genial of chess players. He has the shining good humor that accompanies self-contentment; for he knows all the answers, and is “assured of certain certainties.” He beams optimism over the chess-board. In the Hastings Premier of 1952 he was in the rear of the field. “That Abrahams did badly,” wrote Golombek, “the tournament table shows. But so powerful and full of color is his personality that throughout the tournament I had the impression that either he was in the lead or else engaged in some super-Premier tournament conducted way up above my head at a speed faster than sound and with a brilliance too dazzling for the human eye.”

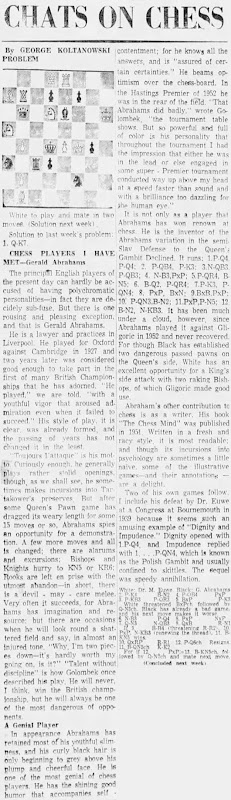

It is not only a player that Abrahams has won renown at chess. He is the inventor of the Abrahams variation in the semi-Slav Defense to the Queen's Gambit Declined. It runs:

1. P-Q4 P-Q4

2. P-QB4 P-K3

3. N-QB3 P-QB3

4. N-B3 PxP

5. P-QR4 B-N5

6. B-Q2 P-QR4

7. P-K3 P-QN4

8. PxP BxN

9. BxB PxP

10. P-QN3 B-N2

11. PxP P-N5

12. B-N2 N-KB3

It has been much under a cloud, however, since Abrahams played it against Gligoric in 1952 and never recovered. For though Black has established two dangerous passed pawns on the Queen's side, White has an excellent opportunity for a King's side attack with two ranking Bishops, of which Gligoric made good use.

Abrahams's other contribution to chess is as a writer. His book “The Chess Mind” was published in 1951. Written in a fresh and racy style, it is most readable; and though its incursions into psychology are sometimes a little naive, some of the illustrative games—and their annotating—are a delight.

Two of his own games follow. I include his defeat by Dr. Euwe at a Congress at Bournemouth in 1939 because it seems such an amusing example of “Dignity and Impudence.” Dignity opened with 1. P-Q4, and Impudence replied with 1. … P-QN4, which is known as the Polish Gambit and usually confined to skittles. The sequel was speedy annihilation.